Photography has been his abiding passion for the past 40 years. His iconic works are currently on display at a retrospective in the National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi. Roopinder Singh takes a look at the world of Raghu Rai and his frames

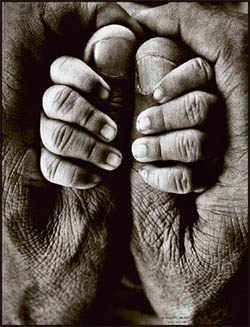

My Father and My Son, a stark, black and white 1969 image of a child grasping the hands of his father, shot by Raghu Rai in Delhi, appears to capture the world as you enter the National Gallery of Modern Art at New Delhi.

What a beautiful moment in time, captured by India’s foremost photojournalist, you feel, as you proceed to explore the journey of a man whose 40 years of work as a photographer are being celebrated by the retrospective titled A Journey of a Moment in Time: Raghu Rai. It is the first that a retrospective of a photographer is being held at the gallery.

The exhibition, on till April 15, has allowed the lensman several independent spaces, depicting his journey of the moment. On display are 185 exhibits captured by the iconic photographer.

Movement marks the picture taken at Churchgate, Mumbai’s famous railway station. It captures the stream of humanity on the platform. You can feel the energy and contrast it with the clarity and stillness of the commuters who are not in a rush.

How well he captures people—a glowering, cigar-smoking Bal Thackeray; Mother Teresa, the very picture of piety; the intense eyes of Satyajit Ray; the serenity of the Dalai Lama, and the power as well as loneliness that emanated from Indira Gandhi. In some images you see the sycophancy that comes with politics.

Rai, 66, captures slices of life in a unique way. You see a couple flirting on a Calcutta rooftop; the interaction of people in a Rajasthani village, or the one photograph that brings home the Bhopal gas tragedy, Burial of an Unknown Child. You literally hear notes of music as you go to his section on musicians of India. Music, Rai says, has been a lifelong passion. He is now working on a book on musicians.

Rai’s very first photograph, of a donkey, was published in The Times, London, in 1966. The photograph occupies pride of place in the exhibition, and he says it was taken at the village of The Tribune’s Chief Photographer, the late Yog Joy, near Rohtak. The animal also comes again in another recent frame: Donkeys on Kargil Heights Rai has extensively documented the Sikhs, and even brought out a book by the same title, with the text by Khushwant Singh. He has 18 books to his credit, including Raghu Rai’s Delhi, Calcutta, Khajuraho, Taj Mahal, Tibet in Exile, India, and Mother Teresa.

Soon after the Retrospective was inaugurated, Rai “escaped” to Anandpur Sahib to revisit the Hola Mohalla festival, which he also covered in the 1970s as well as in 2002. He has photographed the Sikhs extensively, capturing their traditions, customs, as well as the traumas faced by them.

“India is a multi-religious, multicultural society in which several centuries live together at the same time. The experience of India has to be multi-layered and so a moment in time is not enough. The vision is larger, and what is captured is much more than what a photographs shows,” said Rai, explaining each frame in an unhurried, intense manner.

At a Nihang Camp, Punjab 2001 gives a feel of the centuries that co-exist in India as well as the panorama format that Rai says is very important to his work now.

“When you are young, you look for pretty things. You look for small areas, small spaces, small experiences. As you evolve as a human being, you start seeing more and you want to capture more. My panoramics are my most recent and important work because in them I capture much more than what a photograph normally can. In pictures, often there is a thing happening, sometimes a thing with atmosphere. In these, I capture many expressions. Explaining the picture of a Punjabi wedding, he points out the wistful expression on the face of the groom, and the queer way in which the bride and her sister are interacting, all captured in a single frame.

Even his landscapes have a sense of drama. Ladakh and Lakshadweep harmoniously come together when put together in adjoining frames and as you admire a picture of stormy clouds, Rai says: “We were flying in a helicopter and a storm was approaching. I took a few photographs and moments later, the helicopter was buffeted by strong winds and we barely, made it.”

Rai’s journey, as seen through this retrospective, takes us beyond A Moment in Time. When he is shooting, Rai says, “the emergence of the unseen and the revelation of the unknown leaves me amazed.” He could well be articulating the reaction of many others who experience India through Raghu Rai’s photographs.

I don’t believe in nostalgic nonsense

Raghu Rai was born in 1942 in a village in the Jhang area of Pakistan. He spent some part of his youth in Rohtak and became an engineer. However, he had been initiated into photography by his elder brother, S Paul, and it became his abiding passion since the 1960s. He joined The Statesman as its chief photographer. He was inducted into Magnum Photos in 1977 by legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, who saw Rai’s photographs at an exhibition in Paris. Rai also worked for Sunday and India Today.

Excerpts from an interview with the photographer:

On colour vs B&W

It’s far more difficult to make a successful photograph in colour than in black and white. Each colour has its physical response, its emotional response and if all the colours put together don’t gel, they make a khichdi of colour. To get a strong image going in colour, we have to find colours with which the place blends in and which enhance its emotional response. To understand and respond to colour is difficult. Basically, human mind wants convenience. We see everything in colour, so when you put a black and white filter on life, it silences the noise of colour. It’s far easier to make a good black and white picture and it is far easier to appreciate the black and white picture.

Switch to digital technology

I don’t believe in nostalgic nonsense and technology is something that you are using to express yourself. Now, the technology of film was very cumbersome. When you shot using film, you were not sure about the results till it was developed and if your developer mucked it up, you had no recourse left.

Technology is your tool and new technology gives you greater freedom and greater control in doing your work. Creativity means looking at the world with a fresh eye, giving something new, not repeating the past`85why would you hang on to old technology then? You have to move with time and make a difference with your expression.

The day I started taking pictures on a digital camera, about four years ago, I couldn’t go back to using film. It is so much better, and then you have the ability to click a picture and see it right then.

I still use film for my panoramic cameras because there is no digital camera available for it, when I get one, I will switch.

His Rohtak connection

My father was posted in Rohtak. A kind of beginning was made then. I learnt from my brother S Paul. Yog Joy and I interacted with the proprietor of Grover Studio there.

I never wanted to be a photographer. I had great love for music, but my father wanted me to be an engineer, which I did. I took up a government job for a year, and then came to Delhi. When I was staying with my brother, I came back to photography.

Advice for youngsters

Don’t take all those good pictures that you have seen before. We are human machines which get programmed each day. When we are young, our parents are doing it to us; in school, our teachers do it; our neighbours do it. You need to de-programme your mind, your thinking, your attitude, your mindset. Youngsters should look for their own kind of voice.

— Photos by Raghu Rai

This article was published in The Tribune on March 29, 2008