Rahul Singh has penned an engaging biography of his father Khushwant Singh, says Roopinder Singh.

In The Name of the Father

by Rahul Singh. Roli Books, Delhi. Pages 144. Rs 395.

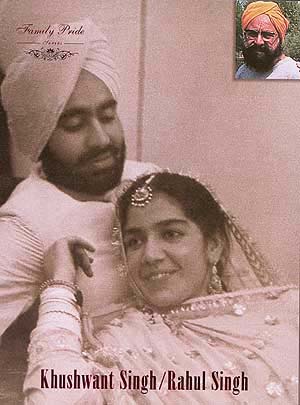

Khushwant Singh and Kaval Malik soon after their marriage |

KHUSHWANT SINGH, the man and his writing, what he exposes of himself, fascinate the readers of his columns. They far outnumber the readers of his books, over which, one suspects, he labours much more. To say that Khushwant Singh’s life is an open book is a cliché. He has written so much about himself that there is hardly a facet of his life that his fans are not familiar with.

Rahul Singh, himself an author and editor of repute, has produced a book on Khushwant Singh. The DNA is the same, both father and son handle the English language with felicity, and give the readers an effortless text; yet the differences in the treatment of people are significant.

Rahul Singh writes about his father much as a son is expected to, a fair blend of intimacy, respect (it does come through) and familiarity. The sentences propel the reader on to the next page, and the next thereafter, a refreshing change from the complicated, can one say convoluted, constructs of recent writing in India.

The book is also the story of a family, the shadow of which falls over large areas of prime real estate in Delhi. Khushwant Singh’s father, Sir Sobha Singh, made his fortune in building Delhi; the son wrote about the city in a memorable, controversial novel.

His childhood was spent with his grandparents, his days in Modern School, Delhi, “where he was not too good either at studies or in games”; Khushwant Singh the Stephanian, managed admission to King’s College, London University, because “neither Oxford nor Cambridge would admit anyone with a third division.”

Khushwant Singh’s childhood was spent in a religious atmosphere. The book attributes his love of listening to Gurbani every day, and his maintaining the distinctive symbols of his faith, even as he maintains the position of an agnostic to this fact. It was the discovery, by his mother-in-law-to-be, of a book of Sikh hymns under his pillow that turned the vote in his favour while he was wooing the much-sought-after Kaval Malik.

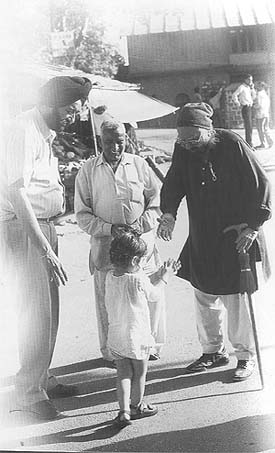

The writer exchanges greetings during his morning walk in Kasauli |

Religion runs deep in us, even as we seek to negate it, and Rahul Singh’s account of the hurt that his parents experienced when he cut his hair while in London will bring a lump in the throat of many a Sikh parent who has faced a similar situation. He returned his Padma Bhushan in protest against Operation Bluestar.

Khushwant Singh, the indifferent student and a prankster, the advocate who would not pay touts to get business, the diplomat who chaffed under Krishna Menon’s bossiness in London, the journalist who joined the profession, to quote his son, after Rahul, and the man who had done memorable translations of the Japjiand written a well-regarded History of the Sikhs, are all facets of the man who has written more about his life and most others. Rahul Singh brings them out in a well-written, neat and short account.

Of course, the pictures of Khushwant Singh’s wife, Kaval, show a strikingly beautiful woman. No wonder she always attracted men, something Rahul deals with candour, discretion and without malice. He also brings out her large-heartedness and the account of her last days says a lot because it is understated.

Rahul’s sister, Mala, and her daughter, Naina, figure prominently, though one would have liked to know more about other members of the family—his uncles, aunts and cousins, and even Rahul. We come across many of the characters we have met earlier in his columns. N. Iqbal Singh, who was familiar to the readers of The Tribune, the Mangatrai’s, Giani Zail Singh, the Zakarias, but they are the supporting cast, as Rahul Singh unfolds the story of his father, and he is rather even handed in handling relationships spoilt by Khushwant Singh, putting to print something that hurt someone quite dear to him.

Family photographs flesh out the narrative, which this reviewer read at one go. They add so much life to the early years of Khushwant Singh, since we are familiar with the face that we see now, not the well-turned out Sardar we see in these photos. Both Rahul Singh and Khushwant Singh tried to get into the Indian Civil Services—ICS and IAS, respectively—and both did not manage. Kismat. They wielded the pen much more effectively than they might have pushing files and fighting through red tape.

This review was published in The Tribune on May 23, 2004