Helium by Jaspreet Singh

Bloomsbury India. Pages 284. Rs 499

Reviewed by Roopinder Singh

RAJ KUMAR is a chemistry teacher at Cornell University. Like so many Indians, he lives in America and has carved out a life that would be envied by many. His success at work does not extend to his personal life. Now divorced, he comes back to India after 25 years to work out his demons, particularly those that connect him to a dark past.

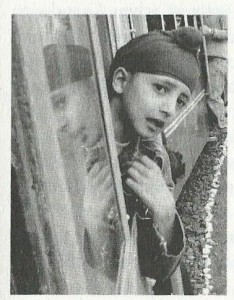

RAJ KUMAR is a chemistry teacher at Cornell University. Like so many Indians, he lives in America and has carved out a life that would be envied by many. His success at work does not extend to his personal life. Now divorced, he comes back to India after 25 years to work out his demons, particularly those that connect him to a dark past.The year 1984. That time when the world turned upside down for Sikhs in many parts of India, particularly in Delhi. When many friends turned foe; when some mothers were told that the only agony they could be saved from was that of seeing their children die; when so many lay dead on the streets of New Delhi, in the very avenues that had provided them and once nurtured them and their families. Professor Mohan Singh, Raj’s teacher, was one of them, and Raj did nothing to stop his death. Would it have mattered? Could his powerful father have done something? Many others did, risking their lives in the process.

As we turn the pages of this book, we go on a journey that meanders along paths less taken. We also gain insights into lives of people like Primo Michele Levi, the Auschwitz survivor whose The Periodic Table is considered one of the most significant scientific books ever written. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s presence is felt. Quite early in the narrative one is aware that this is no linear narration of events — it is nuanced, and edgy.

As Raj explores the elements of memories we see some of the pain and issues that many of those affected by the violence would have felt. While memories may be coloured by the personality of the person who bears them, their emotive content makes others connect with them. For many, the emotions of 1984 are still too raw, as Raj finds out when he visits Professor Singh’s wife Nelly… once the centre of attraction for Raj and his fellow students, his lover and the woman whose world was shattered by the death of her husband, whose daughter was killed and whose son vanished. While Nelly has tucked away the horrors of the atrocities she suffered, they took their toll on her. She is still haunted by the past.

Raj’s father, a senior police officer who lives in splendour in his elite Amrita Sher-gil Marg house, seems to have weathered the event. Yes, as Nelly says in the book, “Service people cannot afford such houses. Such houses come to one either through inheritance or through high levels of corruption.” He is sought after even as he has retired from service, but we soon see how 1984 affected his life. The bridge that Raj’s estranged wife Clara builds with his father is ultimately reduced to an exchange of “polite meaningless words every couple of months.”

The author uses flashbacks to bring the shadows of the past into the present. We learn much as he and Nelly interact, we find out about his friend who was the only person to step up and try to defend Professor Singh. He is still traumatised by what happened. Nelly fills in many blanks in Raj’s attempt to reconstruct the life of his mentor… and his own. He was involved with her. He was selfish, but he was very much in love with her. Raj discovers much more about what happened to Nelly not only from her, but also others, including a friend of his father, a police officer whose conscience led him to break an old relationship.

The author uses flashbacks to bring the shadows of the past into the present. We learn much as he and Nelly interact, we find out about his friend who was the only person to step up and try to defend Professor Singh. He is still traumatised by what happened. Nelly fills in many blanks in Raj’s attempt to reconstruct the life of his mentor… and his own. He was involved with her. He was selfish, but he was very much in love with her. Raj discovers much more about what happened to Nelly not only from her, but also others, including a friend of his father, a police officer whose conscience led him to break an old relationship.

He finds out how the mobs used buses and had voters’ lists, about the local leaders who led the mobs… and prospered thereafter, about the horrific ways in which man turned against man, something that continues to haunt us through centuries of our “civilised” existence.

Raj’s return to his roots is a journey of exploration into a past made more difficult because of the dismal rate of conviction of those who perpetuated atrocities on their fellow human beings, and also because of a collective amnesia that moving on appears to demand from those who suffered.

The Canada-based author has used elements of science, philosophy and chemistry to pen a disturbing portrait of what is just one instance of a “Periodic Table of Hate” that erupts in India, and the rest of the world. The author joins others who have made readers take a difficult journey. Raj describes himself as a specialist in rheology, “the science of deformation and flow”. Even as the reader struggles with the flow of the book and comes to terms with the deformations it exposes, it is obvious that this is not an easy read. But then, such books seldom are.

This review was published in The Tribune on March 16, 2014