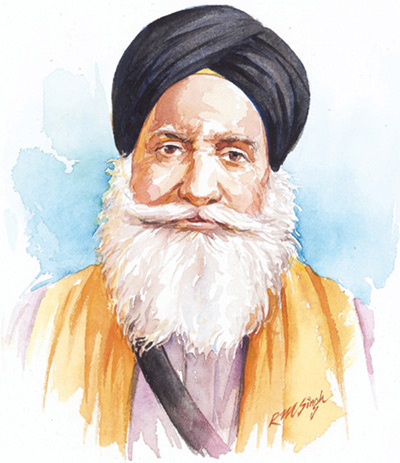

The Uncrowned king

By Roopinder Singh

Baba Kharak Singh Marg is situated in the heart of New Delhi. People from all over the world go there hunting for handicrafts at emporiums of different states, including Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh. But who is this Baba after whom this important road in the nation’s Capital has been named?

What was his role in India’s freedom movement? Why did free India’s rulers decide to rename the famous Irwin Road as Baba Kharak Singh Marg? Lord Irwin was a Viceroy of British India (of the Gandhi-Irwin Pact fame).

Diving from Connaught Place towards Rashtrapati Bhavan recently, I saw a Nihang Sikh crossing Baba Kharak Singh Marg. I asked him if he knew anything about the Baba. He replied: “Beta, Baba ji Sikhan de betaj Badshah san.” (Son, Babaji was the uncrowned king of the Sikhs). A politician who spurned positions, perks and privileges Baba Kharak Singh (1867-1963) was often addressed by this title.

To quote Khushwant Singh: “In the history of every nation. Some figures stand out as landmarks by whose presence we recognise the events of time– Baba Kharak Singh is such a landmark–not only in the history of the history of the Sikhs, but that of India itself.”

“Baba Kharak Singh’s name is associated with the birth of political consciousness in Punjab, its maturing into a movement and the first triumph of the experiment of passive resistance to be carried out in India. He is the most important Sikh character of the Indo-British history.”

An aristocratic lineage and his family’s good relations with the British (Baba Kharak Singh’s father and his elder brother held the titles of Rai Bahadur), did not prevent this well-educated man (the Baba was among the first graduates from Panjab University, Lahore, in 1899) from joining the freedom struggle.

What made him give up a comfortable and privileged lifestyle and opt long terms in prisons? In a word –patriotism.

Baba Kharak Singh’s long public life began innocuously enough — when he was elected Chairman of the Reception Committee of the fifth session of the All-India Sikh Conference held in his home town, Sialkot, in 1912.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919 and the subsequent events in Punjab under Martial Law galvanised him into political activity. He addressed the annual session of the Indian National Congress which was held as Amritsar in December 1919, under the presidentship of Motilal Nehru.

Baba Kharak Singh was elected the first President of the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabhandak Committee (SGPC) in 1921. In November that year, the Punjab Government passed as order where by the keys of the toshakhana (treasury) of the Golden Temple at Amritsar were to remain in the custody of the Deputy Commissioner of the district.

The SGPC protested and an agitation was launched. Baba Kharak Singh was arrested. The agitation continued.

As Rana Jang Bahadur Singh, a former Editor of The Tribune wrote: “Ultimately the proud ruling power had to bend before the iron will of the puissant Baba. The key was delivered to him at a public function by a representative of British imperialism. And, metaphorically speaking with that key he eventually opened the gates of the temple of freedom. He became a general of the army of liberators in the Punjab and his life became a saga of sustained, valiant struggle.”

On January 17, 1922, the keys of the Golden Temple were handed back to Baba Kharak Singh, who had been released along with thousands of other political prisoners, at Akal Takht. On this day Mahatma Gandhi, who was then ‘Dictator’ of the Indian National Congress, sent the following telegram to Baba Kharak Singh: “First decisive battle for India’s freedom won. Congratulations.”

In February, 1922, Lala Lajpat Rai, who was then President of the Punjab Provincial Congress was imprisoned. Baba Kharak Singh was elected the new President. Commenting on this move, Mahatma Gandhi wrote in Young India: “I congratulate the Punjab Provincial Congress Committee on its decision to elect Sardar Sahib. It is indeed an excellent choice.”

“In the days of our struggle for freedom, he was a pillar of strength and no threat of coercion could bend his iron will. By his example, he inspired innumerable persons,” Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said on the occasion of the 86th birthday of Baba Kharak Singh.

The Morcha for Gandhi cap is a good illustration of this statement. While Baba Kharak Singh, along with Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, was among the 40 prisoners held in Dera Baba Ghazi Khan Jail, the British jail authorities issued an order under which political prisoners were not allowed to wear anything which formed a part of their national dress.

Thus Sikhs could not wear black turban (the Sikh symbol of protest since the Nankana Sahib tragedy) and Hindus as well as Muslim could not wear Gandhi caps.

Led by the Baba, the prisoners decided to violate the ban. When a month or so later, in January, 1923, the inspector General of Prisoners came on an inspection, the political prisoners wore their black turbans or Gandhi caps.

The enraged British authorities forcibly removed the turban from Baba Kharak Singh’s head. At this, the prisoners refused to wear their clothes. The Sikhs vowed to wear only their kacheras and the Hindus their dhotis till the ban was lifted.

Baba Kharak Singh was to remain in jail for five and a half years till the Punjab Legislative Council unanimously passed a resolution to release him in 1927.

While in jail, he was offered various inducements to change his stance and start wearing clothes. The British even tried the famous –divide and rule– tactics by allowing the wearing of the turbans, not Gandhi caps.

The Baba remained unfazed and unmoved. His sentence was increased several times for defying the ban. He was even incarcerated in the ‘condemned cell’ where those who have been awarded the death sentence are kept, but he refused to bend or compromise.

An iron will and firm convictions marked out Baba Kharak Singh from the rest. While the Congress party accepted Dominion status as a first step towards the achievement of independence in1929, this man refused to compromise.

When Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya went to Baba Kharak Singh to request Baba Kharak Singh to give his support for the ‘Nehru Report’ which accepted Dominion status, the Baba said: “Panditji, I respect you but how can I accept semi-slavery?” Baba Kharak Singh did not bend and eventually the Congress revised its decision.

President Rajendra Prasad, writing about Baba Kharak Singh later said: “In the midst of fluid alignments and changing politics which swept many a patriot off his feet, Baba Kharak Singh ever remained steadfast to his convictions of sturdy and secular nationalism.”

After Partition, Baba Kharak Singh settled down in Delhi. He refused offers for any position and became an elder statesman of the nation and the Sikhs.

As Gurdit Singh Jolly, a 93 years old veteran freedom fighter who was a close associate of Baba Kharak Singh, recalled in a firm voice which belied his years:

“We could not celebrate the 84th birthday of Baba ji’s because of this ill-health. Pandit Nehru came to Baba Kharak Singh’s house near the Old Secretariat in Delhi, at 9:30 a.m. to greet Baba ji.

“We received the PM and ushered him to the drawing room where Baba ji was sitting. After the exchange of greetings, Nehru said: ‘To whom has this house been allotted?’

“Sant Singh Layalpuri said that the house had been allotted Baba ji’s grandson to compensate the loss suffered by the family in Pakistan (Baba ji’s son died in 1947 in a car accident in the Kuku valley)

“Nehru said: ‘Baba ji aap ke — before he could complete the sentence, Baba Kharak Singh snapped back:’Jawahar, mere ko kharidne aye ho?’ Jawaharlal Nehru was left speechless,” recalled Mr. Jolly, who witnessed the exchange, when I met him in New Delhi recently.

Two years earlier, on June 6, 1949, Nehru presented Baba Kharak Singh with a silver replica of the National Flag at a public function held to commemorate his birthday.

He had then said: “There are few hands which can uphold the honour and preserve the dignity of the National Flag better than those of Baba ji’s. Baba Kharak Singh’s record of honesty and integrity could not be easily equalled.”

Baba Kharak Singh died on October 6, 1963. Even in his death, he caused a stir.

“Pandit Nehru was in Parliament when he heard that Baba Kharak Singh had passed away. He rushed from Parliament to be by his bedside.

“When he arrived there he saw that Baba ji was still struggling. Nehru was angry at having to rush out on the midst of a Parliament session and he asked the doctors for an explanation. ‘Well technically he is dead. But this is some kind of a struggle going on within him,’ said the doctors. There he was, struggling till the very last”, recalls Mr. Jolly.

It is interesting to see how perceptive Baba Kharak Singh was. On July 10,1949. In an appeal to the nation he said:

“It is a matter of genuine pride that India has become free from foreign domination and I pray the Providence to bless my motherland with lasting prosperity and biding peace.

“But I regret to say that the lot of the common man in India has not much improved as it should have under the national government. Our Prime Minister (Nehru) is truly a great man worthy of the position that he hold, but I regret to observe that most of the things that he intends to do for the country’s good and many a declaration of policy he makes are nor fully implemented by those who are doing the day-to-day administration.

“Black marketing, corruption, jobbery (fraudulent official transactions) and several other vices are rampant both in the administration as well as outside. I am afraid that if drastic steps are not taken immediately and of nothing substantial is done effectively to stem this vicious tide, our hard-won freedom will be of little use.”

Baba Kharak Singh was describing the Indian scene of four decades ago. His advice still holds good, but just as it did not have much affect on those who were eulogising him then, it will have little impact on those who are in the power now.

March 29, 1993